My Latest Net-Nets: Castor Maritime & Toro Corp

Two profitable Net-Nets trading at 22% and 35% of net cash.

A few weeks ago, I came across two intriguing net-net opportunities: Castor Maritime and Toro Corp. Both companies are trading well below their net cash positions, which caught my attention.

Castor Maritime:

Market Cap: $40 million

Cash & Cash Equivalents: $230 million

Total Liabilities: $50 million

Net Cash: $180 million

Castor is currently trading at just 22% of its net cash. A similar situation is found with Toro Corp:

Toro Corp:

Market Cap: $65 million

Cash & Cash Equivalents: $190 million

Total Liabilities: $5 million

Net Cash: $185 million

Toro is trading at 35% of its net cash position.

Given these significant discounts, one might assume these are terrible businesses burning cash rapidly. However, that has not been the case at least in the past. Both companies operate in the maritime industry, which is known for its extreme cyclicality and unpredictability, but they've both been profitable. Additionally, Toro has $88.7 million worth of vessels on its balance sheet, while Castor has $173.4 million in vessels.

Financial Performance:

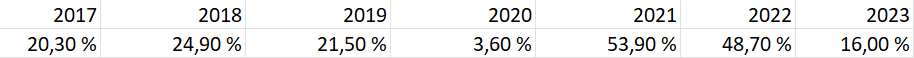

Castors operating margins historically :

In the first half of 2024, Castor reported a net income of ~$44 million, which included $19.3 million from the sale of vessels and $18.5 million in "Other income," primarily from gains on its preferred shares in Toro. Even excluding these one-time items, Castor generated nearly $6 million in net income. In 2023 and 2022, Castor produced $23.2 million and $118 million in net income, respectively, excluding vessel sales and investment gains.

Toro was spun off from Castor in 2022, so its profitability data is limited. In 2023 and 2022, Toro generated $38 million and $47 million in net income (excluding vessel sales). However, over the past six months, Toro barely broke even.

Red Flags to Consider:

While these numbers seem compelling, there are some potential risks:

Incorporation in the Marshall Islands: Both companies are incorporated in the Marshall Islands, which is common in the maritime industry due to favorable tax structures and ease of incorporation. However, this comes with downsides, such as weaker corporate governance and fewer legal precedents.

Shareholder Dilution: Castor has a history of diluting shareholders significantly. During 2021 they diluted shareholders to be able to finance their fleet expansion as freight rates increased. While Toro recently bought back some shares, it's possible they could issue more stock to raise cash for fleet expansion.

Preferred Shares Structure:

When Toro Corp. was spun out of Castor Maritime, both companies issued preferred shares to each other. Castor holds $140 million in Toro's preferred shares, paying a 1% annual dividend, non-convertible until 2026.

Toro, in turn, owns $50 million in Castor's preferred shares, paying a 5% annual dividend. These preferred shares can be converted into common stock at prices between $3 and $7, which would result in a potential 170% to 75% dilution of Castor. Additionally, both preferred shares' dividend rates will increase by 30% per quarter after the seventh year, capped at a 20% annual yield.

Leadership Concerns:

Petros Panagiotis serves as the CEO of both Toro and Castor. He owns 50% of Toro, and while he does not directly own shares in Castor, he controls it through Thalassa Investment Co. S.A., which holds significant preferred shares in Castor. This gives Panagiotidis influence over Castor's shareholder voting outcomes.

Some speculate that this structure incentivizes Panagiotidis to lower Castor's share price to $3, allowing Toro to convert its preferred shares at a lower price and maximize his stake in Toro. Although this is a risk, one potential strategy for investors could be owning shares in both companies to hedge against the dilution or just bet in Toro where Panagiotidis has his money.

However, this financial arrangement is uncommon and raises concerns about Panagiotidis' potential to engage in financial engineering to prioritize his own profits. Additionally, he is CFO and Chairman of both companies, Panagiotidis has near-total control, and the limited publicly available information on him further complicates the ability to fully understand his motivations and the future of these businesses.

Why These Companies Trade at a Discount:

Illiquidity: Both stocks have low trading volumes.

Cyclicality: The maritime industry is highly cyclical, and many investors shy away from such volatility.

Complex Shareholder Structures: The complicated preferred shares and dilution risks might scare off investors.

Lack of Investor Attention: These companies may simply be overlooked by the broader market.

Maritime Industry Outlook:

The future of the maritime industry is uncertain. During the pandemic, demand for vessels skyrocketed, driving up charter rates. This prompted many maritime companies to place orders for new ships. In addition, geopolitical conflicts, like disruptions in the Suez Canal and Red Sea, increased demand for vessels as routes had to go around Africa. However, as global demand for goods normalizes post-pandemic and trade routes stabilize, there could be an oversupply of vessels, leading to lower freight rates and tighter margins.

Also, with ship prices currently at historic highs due to demand, Panagiotis seems to be capitalizing on this by selling off much of both Toro’s and Castor’s fleets.

Conclusion:

Both Castor Maritime and Toro Corp present compelling net-net opportunities, trading well below their net cash positions. However, they come with significant risks, including shareholder dilution, leadership concerns, and the inherent cyclicality of the maritime industry. Despite these risks, their strong balance sheets and recent profitability make them interesting cases for further investigation.

Typically when I consider net-net's from Ben graham's approach, I deduct the value of preferred shares, so Toro is not a net-net, but Castor Maritime appears to be